Flow-Based Programming: Seminal Texts & Theoretical Foundations

A research brief prepared by repolex.ai in conjunction with ASIMOV Systems

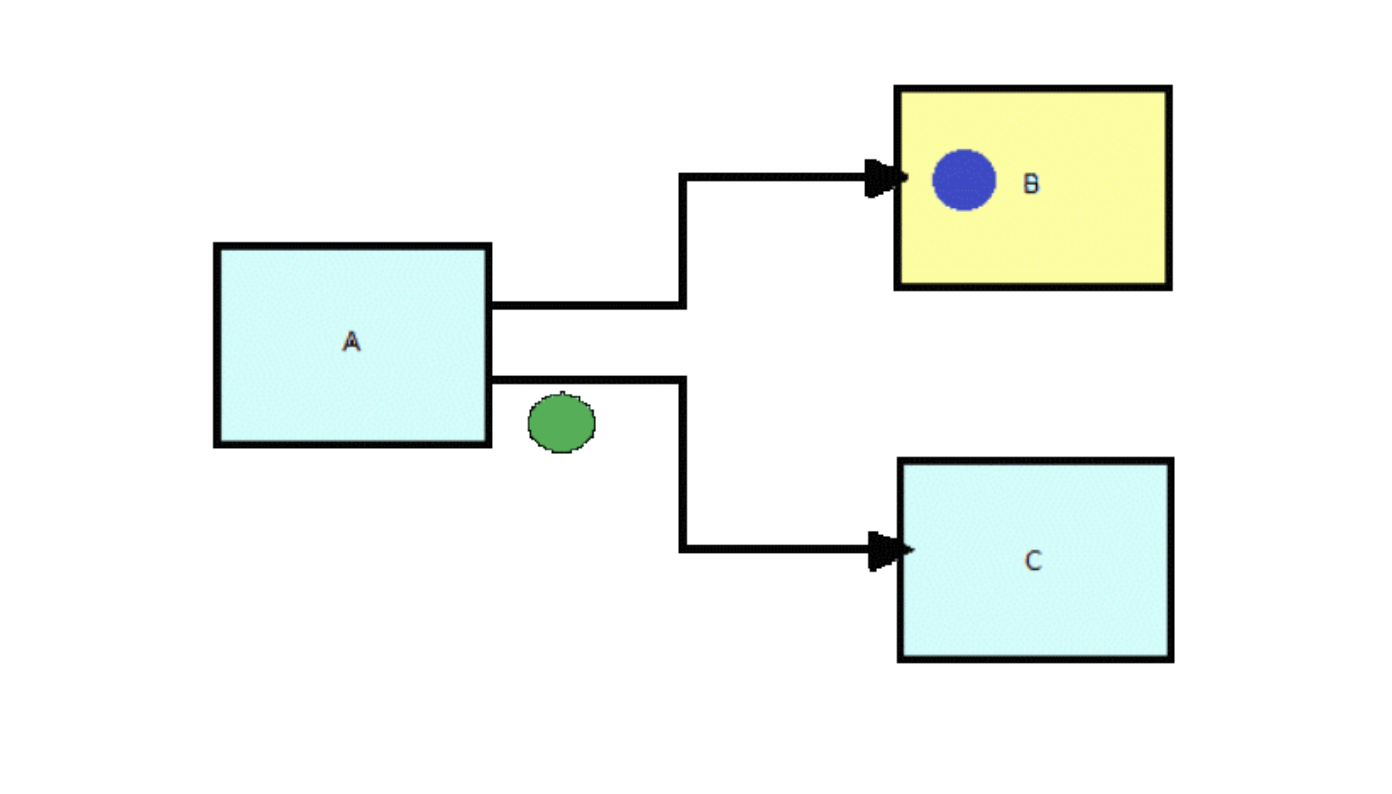

Flow-Based Programming (FBP) represents one of the most prescient yet underutilized paradigms in computing history. Invented by J. Paul Morrison at IBM in the early 1970s, FBP anticipated by decades the architectural patterns now dominating modern software: microservices, stream processing, reactive systems, and visual programming environments.

The convergence of AI-assisted development, semantic web technologies, and the demand for compositional, auditable systems creates an unprecedented opportunity to resurrect and extend Morrison’s vision. FBP’s inherent properties—deterministic concurrency, visual representation, and component reusability—align precisely with the requirements of next-generation software infrastructure.

The Origin Text

Flow-Based Programming: A New Approach to Application Development

Morrison, J. Paul. Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1994. 2nd Edition: CreateSpace, 2010.

This is the definitive text on FBP, written by its inventor after two decades of practical application at IBM and other organizations. Morrison developed FBP (originally called “Data Flow”) while working on batch processing systems for a Canadian bank in 1969-1971, discovering that decomposing applications into networks of asynchronous processes connected by bounded buffers produced systems that were easier to understand, maintain, and modify than conventional procedural code.

Key contributions of this text include the formalization of Information Packets (IPs) as first-class data entities with defined lifecycles, the concept of bounded buffers providing natural backpressure, and the separation of network topology from component implementation. Morrison demonstrates how the same components can be rewired without modification to solve different problems—a compositionality that remains elusive in most programming paradigms.

Theoretical Foundations

Kahn Process Networks

Kahn, Gilles. “The Semantics of a Simple Language for Parallel Programming.” Information Processing 74, North-Holland Publishing, 1974.

Gilles Kahn’s foundational paper provides the mathematical semantics that underpin FBP’s determinism. Kahn proved that networks of monotonic processes communicating through unbounded FIFO channels produce deterministic results regardless of scheduling—a profound result that distinguishes FBP from other concurrent programming models. While Morrison developed FBP independently, Kahn’s theoretical framework provides the formal basis for reasoning about FBP network behavior.

The key insight is that Kahn networks are confluent: no matter how processes are interleaved, the same inputs produce the same outputs. This property is essential for debugging, testing, and formal verification—capabilities increasingly demanded in safety-critical and regulated domains.

Communicating Sequential Processes

Hoare, C.A.R. “Communicating Sequential Processes.” Communications of the ACM, 21(8), 1978.

Tony Hoare’s CSP provides an alternative formal model for process communication that influenced FBP’s development. While CSP uses synchronous rendezvous (both sender and receiver must be ready simultaneously), FBP’s buffered connections provide greater flexibility and natural flow control.

The Actor Model

Hewitt, Carl; Bishop, Peter; Steiger, Richard. “A Universal Modular ACTOR Formalism for Artificial Intelligence.” IJCAI, 1973.

Carl Hewitt’s Actor Model shares FBP’s emphasis on message-passing concurrency but differs in crucial ways. Actors are addressed entities that can create new actors and change behavior between messages, while FBP processes are anonymous components in a fixed topology. FBP’s static network structure enables visual programming and topological reasoning that dynamic actor systems cannot easily support.

Category Theory Connections

String Diagrams and Monoidal Categories

Selinger, Peter. “A Survey of Graphical Languages for Monoidal Categories.” New Structures for Physics, Springer, 2010.

A profound realization emerges when examining FBP through the lens of category theory: FBP networks are string diagrams in monoidal categories. This is not merely an analogy—it is a precise mathematical correspondence. Components are morphisms, wires are objects, parallel composition is the monoidal product, and sequential composition is ordinary categorical composition.

This connection has explosive implications. Category theory provides a unified framework for reasoning about composition across domains—functional programming, quantum computing, linguistics, and control systems all share this mathematical substrate. FBP networks, properly formalized, become a universal computational notation.

Seven Sketches in Compositionality

Fong, Brendan and Spivak, David I. MIT Press, 2019. (Available: arXiv:1803.05316)

This accessible introduction to applied category theory dedicates significant attention to signal flow graphs and their categorical semantics. Fong and Spivak demonstrate how engineering diagrams—including dataflow networks—can be given precise compositional meaning. Their treatment of operads and decorated cospans provides tools for defining domain-specific FBP variants with guaranteed compositional properties.

Dataflow Architecture Research

Static and Dynamic Dataflow

Dennis, Jack B. “First Version of a Data Flow Procedure Language.” MIT, 1974.

Arvind and Nikhil, R.S. “Executing a Program on the MIT Tagged-Token Dataflow Architecture.” IEEE Trans. Computers, 1990.

The dataflow architecture research program at MIT, led by Jack Dennis and later Arvind, pursued hardware implementations of dataflow execution. While commercial dataflow machines never achieved widespread adoption, this research produced invaluable insights into parallel execution models, token matching, and the relationship between program structure and execution semantics. FBP can be understood as a software realization of dataflow principles on conventional hardware.

Systems Engineering Convergence

SysML v2 and Model-Based Systems Engineering

Object Management Group. “SysML v2 Specification.” OMG, 2023.

Elaasar, Maged et al. “The Case for Integrated Model-Centric Engineering.” NASA JPL / OpenCAESAR, 2019.

The systems engineering community has independently converged on flow-based representations through SysML v2’s Action/Flow semantics. Notably, SysML v2’s KerML (Kernel Modeling Language) provides foundational semantics that map to OWL2-DL, enabling integration with semantic web technologies. NASA JPL’s OpenCAESAR project bridges SysML with OML (Ontological Modeling Language), demonstrating the viability of connecting visual dataflow models to RDF-based knowledge graphs.

This convergence is significant: aerospace, defense, and automotive industries are adopting flow-based system representations at scale. FBP provides a computational execution model for these otherwise static diagrams.

Modern Implementations & Validation

Several modern projects have demonstrated FBP’s continued relevance:

- NoFlo (Henri Bergius, 2011-present): JavaScript FBP runtime with visual editor, used in production at The Grid and other companies.

- Node-RED (IBM Emerging Technology, 2013-present): Visual programming tool for IoT and event-driven applications. Deployed globally in industrial and home automation contexts.

- Apache NiFi (NSA/Apache Foundation): Enterprise data flow system handling petabytes at major organizations.

- LabVIEW (National Instruments, 1986-present): Dataflow visual programming for scientific instrumentation. Four decades of continuous development and billions in revenue.

- Unreal Engine Blueprints (Epic Games): Visual scripting system enabling non-programmers to create game logic.

Why Now: The Convergence Thesis

Several technological and market forces create an unprecedented opportunity for FBP-based tools:

-

AI-Assisted Development: Large language models excel at generating isolated components but struggle with architectural coherence. FBP’s separation of topology (network) from behavior (components) allows AI to generate components while humans or higher-level AI systems compose networks—a natural division of labor.

-

Semantic Web Maturity: RDF, OWL, and SPARQL have matured into robust technologies for knowledge representation. FBP networks can be serialized as RDF graphs, enabling semantic querying, reasoning, and integration with enterprise knowledge management systems.

-

Regulatory Pressure: EU AI Act and similar regulations demand explainability and auditability. FBP’s visual representations and deterministic semantics provide natural compliance artifacts that opaque conventional code cannot offer.

-

Microservices Fatigue: Organizations drowning in distributed complexity seek simpler compositional models. FBP offers microservices-like decomposition with principled composition—the benefits without the chaos.

-

Visual Programming Renaissance: Tools like Figma, Notion, and Airtable demonstrate market appetite for visual, composable interfaces. FBP extends this paradigm to computational logic itself.

Conclusion

Flow-Based Programming is not a historical curiosity—it is an idea that arrived decades before its supporting infrastructure. The theoretical foundations are rigorous (Kahn, Hoare, category theory), the practical implementations are validated (NoFlo, Node-RED, NiFi), and the market conditions are favorable. What has been missing is a comprehensive platform that synthesizes these elements: semantic representation, visual authoring, AI-assisted generation, and polyglot execution.

The company that builds this platform will define how the next generation of software is composed, visualized, and understood.

Essential Reading List

Primary Sources

- Morrison, J.P. (2010). Flow-Based Programming, 2nd Edition.

- Kahn, G. (1974). “The Semantics of a Simple Language for Parallel Programming.”

- Hoare, C.A.R. (1978). “Communicating Sequential Processes.”

Theoretical Background

- Fong, B. & Spivak, D. (2019). Seven Sketches in Compositionality.

- Selinger, P. (2010). “A Survey of Graphical Languages for Monoidal Categories.”

- Baez, J. & Stay, M. (2011). “Physics, Topology, Logic and Computation: A Rosetta Stone.”

Online Resources

- J. Paul Morrison’s FBP Website: jpaulmorrison.com/fbp

- NoFlo Project: noflojs.org

- FBP Google Group: groups.google.com/g/flow-based-programming